Esther Williams and Gene Kelly in "Take me out to the Ball Game" (1949) directed by Busby Berkeley

"The All-American man wears a coat of high finance, But the All-American girl wears the pants." -Lyrics from "Take me out to the Ball Game" (1949)

Loretta Young and Alan Ladd in "China" (1943) directed by John Farrow

"I forgot how much trouble an American woman can be," says Alan Ladd in 'China', and there's movie truth in those words. The American woman on film is not a weak creature. She may have a weakness, and it can bring her down; she may be confused and worried, which will cause her to make foolish mistakes; but she is not weak and she is not stupid. Men constantly have to cope with her. She can wreck their dinosaur models, outshoot them in a rifle contest, poison their mushrooms, and reduce them to gibbering idiots. She can, and she does. The American woman on film is too hot to handle. Sometimes the movies make it look as if all of American male culture is focused only on the task of figuring out how to control a force that is stronger than it is, stronger than politics, stronger even than nature: the force of the American woman. 'China' does not end in a close-up of a romantic embrace between Ladd and Young. It doesn't even end by lingering over the dead body of Alan Ladd, the sacrificial hero. It ends with a close-up of Loretta Young's face.

Marilyn Monroe in "The Seven Year Itch" (1955) directed by Billy Wilder

Sexual agenda regarding women takes all forms, from Marilyn Monroe standing over a grate with her skirt blowing up around her to nun Deborah Kerr sleeping alongside marine Robert Mitchum on an isolated island. When Susan Hayward does a wild Gypsy dance in 'Thunder in the Sun' (1959), she is watched by Jeff Chandler. It is a clear metaphor in which a man observes a woman letting herself go, cavorting freely about as an indicator of what she might be like in the act of sex. ("I like the way you dance," leers Chandler.) 'Thunder in the Sun' also has Chandler watch Hayward when she goes down to the river to bathe, swimming naked under his hidden gaze. (This, in fact, is pretty much all the action and excitement there is in the movie.)

In 'China Girl' (1942), Lynn Bari comes to rescue George Montgomery from the Japanese, and the two of them act out a metaphorically abusive relationship. Bari is carrying on her body the gun Montgomery will need to escape. She needs to pass the gun to him in front of his guards. To do so, she first triggers his jealousy. He spits out, "You can't wait for me to be dead so you can take up with these monkeys." She slaps him. He slaps back, hard.

Rosalind Russell in "Tell It to the Judge" (1949) directed by Norman Foster

In 'Tell It to the Judge' (1949), Rosalind Russell can't cook breakfast at the lighthouse. Robert Cummings has thoughtfully provided her with a nice fish to fry, but she can't clean it, cut off its head, or cook it. The viewer can watch him watch her fail and then triumphantly take it away and cook it himself. Spencer Tracy watches with similar amused tolerance in Woman of the Year (1942), while Katharine Hepburn, a world famous newspaperwoman, tries to make pancakes. Even a cup of coffee is beyond her ability. As Hepburn destroys the kitchen, Tracy shows us how to see her incompetence, and then he rescues her. (At least he has the grace to say that anyone can make breakfast. It's her he wants, not a cook.)

Claudette Colbert, Brian Aherne and Ray Milland in "Skylark" (1941) directed by Mark Sandrich.

In "Skylark" (1941), Claudette Colbert falls on her face, slipping all around the floor, as she tries to cook fish in a boat's galley. It is perhaps easy to make too much of these humiliation scenes. In all three cases, the women get their men anyway, and they do not fundamentally change themselves. Russell remains a judge, Colbert remains an elegant wife, and Tracy even lectures Hepburn on the folly of her having felt she should cook.

Comparing Claudette Colbert and Carole Lombard, two stars who often played elegant women in romantic comedies, shows how subtle variations emerge that draw on possible audience differences. No matter what happened to Colbert, she maintained her cool charm, her throaty chuckle, and her ability to emerge a winner.

Even when she was playing a bedraggled poetess on the lain in "It's a Wonderful World" (1939) or was stepping out into a torrential downpour with nothing but a newspaper to shield her gold lamé (Midnight, 1939), she looked perfectly turned out, neat, trim, and competent. Whatever it was, Colbert never stepped in it over her shoe tops. No doubt women yearned for that level of subtle mastery and enjoyed Colbert's triumphs.

Lombard, on the other hand, didn't keep herself above it. She fell into it, taking the pratfall, but remaining a good sport. She might shriek and kick at a man (as she did to John Barrymore in Twentieth Century, 1934) and she might be socked on the jaw (as she was by Fredric March in 'Nothing Sacred', 1937), but somehow she managed to make it look desirable, appropriate, and not demeaning. Although both Lombard and Colbert played in dramas and were considered serious actresses, they were more appreciated for their roles in these sophisticated comedies about women.

Films provide other answers to the question of "What do women want?" "I want things!" cries out Peggy Cummins in "Gun Crazy" (1949), by way of explaining why she and her beloved should embark on a life of crime together. "I want things... big things!" She utters the battle cry of movie females, the anguished bleat for money, sex, freedom, clothes. Give me things. A man's gotta do what a man's gotta do, say movies, but a gal's gotta have what a gal's gotta have, and what a gal's gotta have is things. When women don't have the things they want, they become unhappy, suicidal, even murderous.

"This dime-store china," complains Sheila Bromley to Ronald Reagan in 'Accidents Will Happen' (1939), "it's making an old woman out of me."

Rosa Moline (Bette Davis in "Beyond the Forest", 1949) wakes up in her bed with a satisfied, sensual smile on her face, her equivalent of the Scarlett O'Hara morning after. Realizing that she has indeed aborted and can now marry her lover, she moves deliciously in the bed and picks up her mirror and lipstick to make herself presentable. Her joy is shortlived, as she soon begins to "burn up" inside. After making herself up like a grotesque caricature of a woman, she staggers downtown to board the night train to Chicago in one last attempt to get out of Loyalton, Wisconsin, and to get free of a typical female life. As she approaches the station, the train sits on the tracks, smoking and hissing and belching like the Train to Hell rather than the night train to the Windy City. The train appears to be waiting for her, but like the treacherous male symbol it is, it pulls out and leaves her, abandoning her to her fate. After the train moves out, viewers see Rosa, lying dead alongside the track, having died from the pain of being a woman.

In a perceptive article on the film's director, King Vidor, Eric Sherman says that Vidor "seems not at all concerned that we understand why she [Rosa] is this way," meaning why Rosa Moline is evil, desperate, murderous. Sherman is correct, but from a woman's point of view I would say that females in the audience understand exactly why Rosa Moline is "this way." No construction of an explanation is necessary other than her being a female character played by a woman. Rosa Moline fought on to the end, gallant but misguided, unwilling to accept repression and restriction.

Rosa Moline has called her pregnancy "the mark of death," which is what it will turn out to be for her. She's like Michael Corleone or Frankenstein's monster or Cody Jarrett. She may kill. She may look ugly. She may be something for the birds. But she never quits. Rosa Moline is an American hero.

Sally Forrest and Claire Trevor in "Hard, Fast And Beautiful" (1951) directed by Ida Lupino

Like 'Mildred Pierce' before her, Claire Trevor slaps her own child silly in 'Hard, Fast And Beautiful'. The destructive mother ends up losing her daughter's love and respect, and she also loses her husband.

As she sits at his hospital bedside, the two of them discuss Trevor's life. It's a kind of last chance for the husband to pass judgment, since he will soon die: -"Everything was for Florence, wasn't it? You made yourself believe that, but it was all for you. Nobody but you." -Millie: "No! That isn't true," Will Farley: -"You never gave love. That's the most important thing. You took it, used it, but you never gave an ounce of it to anybody."

Having delivered the death blow to her sense of herself, he suddenly goes as hard as nails, turning into a different man. "Beat it, Millie," he tells her. In the end, Trevor is left totally alone in the frame, in the dark of night in an empty tennis stadium. She sits alone, with abandoned programs and papers blowing about her feet, and nothing but the sound of tennis balls being batted back and forth. This is the fate of the destructive mother, the image warns. -"A Woman's View: How Hollywood Spoke to Women, 1930-1960" by Jeanine Basinger

Sunday, September 08, 2013

Tuesday, September 03, 2013

Jake Gyllenhaal & Matt Damon connection

Jake Gyllenhaal chews on his iPhone headphones while walking around the Soho neighborhood on Thursday afternoon (August 29) in New York City. The 32-year-old actor just secured an appearance on Bravo’s Inside the Actors Studio, according to The Wrap. Jake‘s appearance on the show, which is hosted by James Lipton, will air on Thursday, September 19 at 8/7c. On the episode, he discussed his wide range of films, including the upcoming Prisoners, as well as his famous Hollywood family and his relationship with the late Heath Ledger. Source: www.justjared.com

"The nice thing about ["The Zero Theorem"] is Christoph [Waltz], thanks to Quentin [Tarantino]’s films, has become bankable to a certain level and that was fantastic and that’s how we made it; not because of the ideas but because Christoph and I were able to work together. And then I sweetened the load even more with friends like Tilda [Swinton], Matt Damon, and David Thewlis all coming into play. Source: blogs.indiewire.com

Heath Ledger and Matt Damon in "The Brothers Grimm" (2005) directed by Terry Gilliam

-I remember asking Heath Ledger after Brokeback Mountain, “How’d you do that scene with Jake?” —meaning the scene where they start ferociously kissing. He said, “Well, mate, I drank a half case of beer in my trailer.” I started laughing, and he goes, “No, I’m serious. I needed to just go for it. If you can’t do that, you’re not making the movie.” -Matt Damon in Playboy magazine

Hayden Christensen, Anna Paquin and Jake Gyllenhaal in "This Is Our Youth" (2002)

Casey Affleck, Summer Phoenix and Matt Damon, on Opening Night of "This Is Our Youth" (2002)

"This is our Youth" has seen a number of productions featuring notable film actors, many of whom were in their first stage role. At the Garrick Theatre in the West End, it featured Hayden Christensen, Matt Damon, Colin Hanks, and Chris Klein as Dennis, Jake Gyllenhaal, Casey Affleck, Kieran Culkin, and Freddie Prinze Jr. as Warren, and Anna Paquin, Summer Phoenix, Alison Lohman, Heather Burns as Jessica.

Jake Gyllenhaal and Vera Farmiga, co-stars in "Source Code" (2011)

Vera Farmiga and Matt Damon at "The Departed" New York Premiere (2006)

Gwyneth Paltrow and Jake Gyllenhaal at Hamptons screening of "End of Watch", 2012

Matt Damon and Gwyneth Paltrow attending "Contagion" premiere during the 68th Venice International Film Festival, 2011.

Matt Damon "Something Else" video

"The nice thing about ["The Zero Theorem"] is Christoph [Waltz], thanks to Quentin [Tarantino]’s films, has become bankable to a certain level and that was fantastic and that’s how we made it; not because of the ideas but because Christoph and I were able to work together. And then I sweetened the load even more with friends like Tilda [Swinton], Matt Damon, and David Thewlis all coming into play. Source: blogs.indiewire.com

Heath Ledger and Matt Damon in "The Brothers Grimm" (2005) directed by Terry Gilliam

-I remember asking Heath Ledger after Brokeback Mountain, “How’d you do that scene with Jake?” —meaning the scene where they start ferociously kissing. He said, “Well, mate, I drank a half case of beer in my trailer.” I started laughing, and he goes, “No, I’m serious. I needed to just go for it. If you can’t do that, you’re not making the movie.” -Matt Damon in Playboy magazine

Hayden Christensen, Anna Paquin and Jake Gyllenhaal in "This Is Our Youth" (2002)

Casey Affleck, Summer Phoenix and Matt Damon, on Opening Night of "This Is Our Youth" (2002)

"This is our Youth" has seen a number of productions featuring notable film actors, many of whom were in their first stage role. At the Garrick Theatre in the West End, it featured Hayden Christensen, Matt Damon, Colin Hanks, and Chris Klein as Dennis, Jake Gyllenhaal, Casey Affleck, Kieran Culkin, and Freddie Prinze Jr. as Warren, and Anna Paquin, Summer Phoenix, Alison Lohman, Heather Burns as Jessica.

Jake Gyllenhaal and Vera Farmiga, co-stars in "Source Code" (2011)

Vera Farmiga and Matt Damon at "The Departed" New York Premiere (2006)

Gwyneth Paltrow and Jake Gyllenhaal at Hamptons screening of "End of Watch", 2012

Matt Damon and Gwyneth Paltrow attending "Contagion" premiere during the 68th Venice International Film Festival, 2011.

Matt Damon "Something Else" video

Terry Gilliam's The Zero Theorem (first clip)

The clip from Terry Gilliam's The Zero Theorem first appeared over at Entertainment Weekly, which included accompanying written commentary from Giliam.

The clip features Christoph Waltz as the film's lead character, Qohen Leth, an eccentric and reclusive computer genius plagued with existential angst works on a mysterious project aimed at discovering the purpose of existence -- or the lack thereof -- once and for all. However, it is only once he experiences the power of love and desire that he is able to understand his very reason for being.

Here's how Gilliam sets the scene: The scene is a man going to work and a man leaving the safety of his burnt out chapel and being attacked by the modern world with all of its noises and all of its advertising and all these things that confuse and confound and make us all crazy.

Matt Damon, Mélanie Thierry, David Thewlis, Lucas Hedges, Ben Whishaw and Tilda Swinton co-star and, as of right now, the film does not have a domestic distributor.

The Zero Theorem played the Venice Film Festival over the weekend and the only review I've taken the time to see is over at The Playlist where they weren't over the moon, but seemed to enjoy it. Source: www.ropeofsilicon.com

Sunday, September 01, 2013

"Elysium": Rebooting Paradise’s System (Film Review)

Elysium (2013) is being considered one of the big disappointments this summer both in box office domestic revenue and on the artistic front. Director Neill Blomkamp’s previous effort was the highly celebrated debut District 9 (2009). In Elysium we find a classic dystopia story: we are in the year 2154, when humanity has adopted an extreme social class division. The rich and wealthy have built a new colony in Elysium, a planet outside the Earth’s orbit. A world (inspired by the Stanford Torus) with all the comforts, totally crime-free: luminosity, calm and security. Everyone else, on the other hand, keeps struggling for survival on our planet Earth, which is wrapped in pervading poverty, disease, decay in morality and overpopulation.

Our protagonist, Max Da Costa (Matt Damon) belongs to this second group, and he’s gotten very sick after having been exposed to radiation while working in a robot factory, he has just five days before he will die. Max’s only hope is reaching to Elysium, where laying on a Medbed he can heal his internal damage. Also, Max reconnects with Frey (Alice Braga), his first love never forgotten whose little daughter, Matilda, suffers from leukemia.

While in Elysium, Delacourt, a ruthless defense secretary played by Jodie Foster, tries to protect the space station’s borders. Delacourt is so overzealous in her mission of preserving the well-being of Elysium’s inhabitants, she conspires to overthrow the political regime with the help of mercenary Kruger (a manic Sharlto Copley) and Armadyne’s CEO John Carlyle (William Fichtner). Carlyle develops a program that can dismantle Elysium’s security code and turn her into the new President.

Computer hacker Spider (Wagner Moura) agrees to help Max infiltrate Elysium’s orbit in a clandestine shuttle only if he’s willing to steal John Carlyle’s secret code in order to reboot Elysium’s security systems. Max is fitted with an exoskeleton, hardwired into his brain, and he’ll initiate a journey to defend his survival, and for extension millions of humiliated earthlings.

According with an interview for The Wire, Neill Blomkamp identifies as neither liberal nor conservative, which doesn’t stop people from ascribing all sorts of agendas to him and his films. Blomkamp believes that Earth will someday look a lot like his movie’s dystopian portrayal – a Malthusian catastrophe; how America’s hegemony is slowly eroding en route to a “third world deathbed.”

Despite of the superficial obviousness of the Elysium’s script at some scenes, we cannot disregard the multiple meanings that lie on its hidden symbolism. For example, it’s no coincidence Matt Damon’s character stands for the last Anglo-Saxon white man in Los Angeles and he seems equally alienated from his past criminal background with Latino gangs (his best friend is Julio, played emphatically by Diego Luna) and from his own aspirations of living in Elysium someday. The name ‘Max’ originates from English or German Maxwell or Maximilian, whose meaning is ‘the greatest.’

Although his romantic attraction to Frey is underdeveloped in the plot, there is a hint of a nebulose sexualization of Max and Frey that indicates Matt Damon’s character as merely symbolic towards the second half of the film – an outsider inherently conflicted between his natural impulses and his destiny as final martyr.

The story that triggers Max’s choice of self-sacrifice is Matilda’s tale about an altruistic hippo and a helpless meerkat. Matilda: “The meerkat was hungry. But he was so small. And the other big animals had all the food, cause they can reach the fruits. So he had to watch them eat all the nice foods and berries cause he’s so small. So he made friends with a hippopotamus, so he can stand on the hippopotamus to get all the fruits he wants. And they eat all the fruit together.”

Max cannot avoid to ask Matilda: “What’s in for the hippo?”, but Matilda assures him the hippo is rewarded simply with the meerkat’s friendship. It’s the key metaphor of the film, Elysium representing the hippo figure and Meerkat the destitute Earth.

Ensambling Max’s spinal cord into the exoskeleton can be read as the Christ figure nailed to a futuristic cross. Blomkamp even composes lingering shots showing blood dripping from Damon’s hands, as an allusion to the stigmata. Max tells Frey before he dies “I know why the hippo did it”. It’s a clear reference to the concept of Christian sacrifice needed to save all the sinners on planet Earth.

Yet curiously Elysium‘s humanist message (enhanced immensely by Matt Damon’s performance) could however be interpreted as nihilist if we follow Max’s character arc in a literal way. In the beginning of his journey Max’s only aspirations are selfish and survival-oriented, not attached to any ideal, so his drastic moral evolution can be explained as a side-effect provoked by the lethal dose of radiation he’s suffered. Twirling down a desperate frame of mind, Max could not want to stay alive anymore in such a bleak chaotic world, so he ends committing suicide in the form of retrieving the data loaded inside his brain to liberate the humans and allow their entrance into Elysium – the Paradise.

Article first published as Movie Review: ‘Elysium’: Rebooting Paradise’s System on Blogcritics

Our protagonist, Max Da Costa (Matt Damon) belongs to this second group, and he’s gotten very sick after having been exposed to radiation while working in a robot factory, he has just five days before he will die. Max’s only hope is reaching to Elysium, where laying on a Medbed he can heal his internal damage. Also, Max reconnects with Frey (Alice Braga), his first love never forgotten whose little daughter, Matilda, suffers from leukemia.

While in Elysium, Delacourt, a ruthless defense secretary played by Jodie Foster, tries to protect the space station’s borders. Delacourt is so overzealous in her mission of preserving the well-being of Elysium’s inhabitants, she conspires to overthrow the political regime with the help of mercenary Kruger (a manic Sharlto Copley) and Armadyne’s CEO John Carlyle (William Fichtner). Carlyle develops a program that can dismantle Elysium’s security code and turn her into the new President.

Computer hacker Spider (Wagner Moura) agrees to help Max infiltrate Elysium’s orbit in a clandestine shuttle only if he’s willing to steal John Carlyle’s secret code in order to reboot Elysium’s security systems. Max is fitted with an exoskeleton, hardwired into his brain, and he’ll initiate a journey to defend his survival, and for extension millions of humiliated earthlings.

According with an interview for The Wire, Neill Blomkamp identifies as neither liberal nor conservative, which doesn’t stop people from ascribing all sorts of agendas to him and his films. Blomkamp believes that Earth will someday look a lot like his movie’s dystopian portrayal – a Malthusian catastrophe; how America’s hegemony is slowly eroding en route to a “third world deathbed.”

Despite of the superficial obviousness of the Elysium’s script at some scenes, we cannot disregard the multiple meanings that lie on its hidden symbolism. For example, it’s no coincidence Matt Damon’s character stands for the last Anglo-Saxon white man in Los Angeles and he seems equally alienated from his past criminal background with Latino gangs (his best friend is Julio, played emphatically by Diego Luna) and from his own aspirations of living in Elysium someday. The name ‘Max’ originates from English or German Maxwell or Maximilian, whose meaning is ‘the greatest.’

Although his romantic attraction to Frey is underdeveloped in the plot, there is a hint of a nebulose sexualization of Max and Frey that indicates Matt Damon’s character as merely symbolic towards the second half of the film – an outsider inherently conflicted between his natural impulses and his destiny as final martyr.

The story that triggers Max’s choice of self-sacrifice is Matilda’s tale about an altruistic hippo and a helpless meerkat. Matilda: “The meerkat was hungry. But he was so small. And the other big animals had all the food, cause they can reach the fruits. So he had to watch them eat all the nice foods and berries cause he’s so small. So he made friends with a hippopotamus, so he can stand on the hippopotamus to get all the fruits he wants. And they eat all the fruit together.”

Max cannot avoid to ask Matilda: “What’s in for the hippo?”, but Matilda assures him the hippo is rewarded simply with the meerkat’s friendship. It’s the key metaphor of the film, Elysium representing the hippo figure and Meerkat the destitute Earth.

Ensambling Max’s spinal cord into the exoskeleton can be read as the Christ figure nailed to a futuristic cross. Blomkamp even composes lingering shots showing blood dripping from Damon’s hands, as an allusion to the stigmata. Max tells Frey before he dies “I know why the hippo did it”. It’s a clear reference to the concept of Christian sacrifice needed to save all the sinners on planet Earth.

Yet curiously Elysium‘s humanist message (enhanced immensely by Matt Damon’s performance) could however be interpreted as nihilist if we follow Max’s character arc in a literal way. In the beginning of his journey Max’s only aspirations are selfish and survival-oriented, not attached to any ideal, so his drastic moral evolution can be explained as a side-effect provoked by the lethal dose of radiation he’s suffered. Twirling down a desperate frame of mind, Max could not want to stay alive anymore in such a bleak chaotic world, so he ends committing suicide in the form of retrieving the data loaded inside his brain to liberate the humans and allow their entrance into Elysium – the Paradise.

Article first published as Movie Review: ‘Elysium’: Rebooting Paradise’s System on Blogcritics

Saturday, August 31, 2013

"Prisoners" Telluride Review: Hugh Jackman and Jake Gyllenhaal, GQ Style scans

Scans of Jake Gyllenhaal and Hugh Jackman in Total Film (UK)

As Keller’s interrogation continues in scenes that are gruesome but never exploitative, Villeneuve frequently cuts away to follow the lead police detective (Jake Gyllenhaal), who is pursuing his own investigation that includes questioning Alex’s lonely aunt (Melissa Leo), whose troubled family history may have led her nephew astray.

As the film weaves all the plot and character strands together, the vise tightens. There are some truly scary scenes as new suspects appear and the film twists its way to a dark, mordant conclusion. It’s worth remembering that Incendies, despite its Oscar nomination and excellent reviews, was essentially a high-class melodrama, and that’s the way that Prisoners should be viewed as well. And thanks to the efforts of an expert filmmaking team, it’s a smashingly effective melodrama. Villeneuve enlisted brilliant cinematographer Roger Deakins, who captures the rainy, chilly atmosphere of this Pennsylvania community with visual eloquence. (Pennsylvania was convincingly recreated outside Atlanta.) The editing by Joel Cox and Gary D. Roach, two editors of many of Clint Eastwood’s recent movies, is also first-rate. Although the film runs two and a half hours, there doesn’t seem to be a wasted frame. Source: www.hollywoodreporter.com

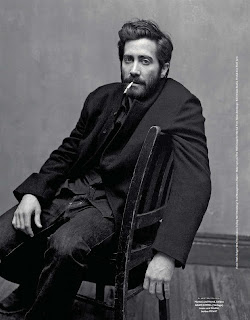

Scans of Jake Gyllenhaal in GQ Style (Germany) magazine, Fall-Winter 2013

As Keller’s interrogation continues in scenes that are gruesome but never exploitative, Villeneuve frequently cuts away to follow the lead police detective (Jake Gyllenhaal), who is pursuing his own investigation that includes questioning Alex’s lonely aunt (Melissa Leo), whose troubled family history may have led her nephew astray.

As the film weaves all the plot and character strands together, the vise tightens. There are some truly scary scenes as new suspects appear and the film twists its way to a dark, mordant conclusion. It’s worth remembering that Incendies, despite its Oscar nomination and excellent reviews, was essentially a high-class melodrama, and that’s the way that Prisoners should be viewed as well. And thanks to the efforts of an expert filmmaking team, it’s a smashingly effective melodrama. Villeneuve enlisted brilliant cinematographer Roger Deakins, who captures the rainy, chilly atmosphere of this Pennsylvania community with visual eloquence. (Pennsylvania was convincingly recreated outside Atlanta.) The editing by Joel Cox and Gary D. Roach, two editors of many of Clint Eastwood’s recent movies, is also first-rate. Although the film runs two and a half hours, there doesn’t seem to be a wasted frame. Source: www.hollywoodreporter.com

Scans of Jake Gyllenhaal in GQ Style (Germany) magazine, Fall-Winter 2013

Happy Anniversary, Fred MacMurray

Happy Anniversary, Fred MacMurray!

Fred MacMurray and Madge Evans in "Men Without Names" (1935) directed by Ralph Murphy.

Fred MacMurray and Madeleine Carroll in "Cafe Society" (1939) directed by Edward H. Griffith

"Honeymoon in Bali" (1939), starring Fred MacMurray & Madeleine Carroll, directed by Edward H. Griffith

"Standing Room Only" (1944), starring Fred MacMurray and Paulette Goddard, directed by Sidney Lanfield

"The Absent-Minded Professor" (1961), starring Fred MacMurray and Nancy Olson, directed by Robert Stevenson.

Fred MacMurray and Madge Evans in "Men Without Names" (1935) directed by Ralph Murphy.

Fred MacMurray and Madeleine Carroll in "Cafe Society" (1939) directed by Edward H. Griffith

"Honeymoon in Bali" (1939), starring Fred MacMurray & Madeleine Carroll, directed by Edward H. Griffith

"Standing Room Only" (1944), starring Fred MacMurray and Paulette Goddard, directed by Sidney Lanfield

"The Absent-Minded Professor" (1961), starring Fred MacMurray and Nancy Olson, directed by Robert Stevenson.

Subscribe to:

Posts

(

Atom

)

_06.jpg)

_01.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)